vol. 1 issue 15

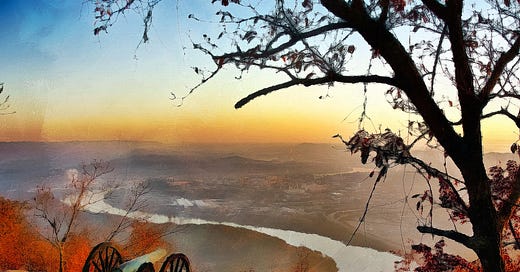

The Battle of Missionary Ridge at Chattanooga. Photo: Brigitte Werner from Pixabay

vol. 1, issue 15

Greetings,

One summer weekend, nearly thirty years ago, I found myself about an hour or so north of Toronto in Barrie, Ontario. I had volunteered to work at the Mariposa Folk Festival where somehow, as a member of the volunteer security tea…